“We issue this call to all milk producers in Michigan to gather at the Michigan Agricultural College, East Lansing, Room 402, Agricultural Building, on Tuesday, May 23, 1916, at 11 a.m.”

The members of the Livingston County Milk Producers’ Association adopted a resolution and meeting notice and shared it with the world via pages of the Hoard’s Dairyman on April 22, 1916.

Four hundred dairy farmers came from all parts of southern Michigan. Some arrived by train in Lansing. Others came in motorcars — such as Ford’s Model T — that had bumped along muddy, deeply rutted wagon roads to get to the campus.

Among this “large and enthusiastic” group were those whose livelihood came primarily from farm enterprises. But Michigan’s dairymen of 1916 also included bankers, statesmen, manufacturers, insurance salesmen and law enforcement officers — men who operated dairy farms while also pursuing other jobs.

Regardless of their background, these men knew how to “get on their feet and state their position with clearness and no little eloquence,” Hoard’s Dairyman reported. “The thought was repeated over and over again that the producer was getting the small end of the horn that his principal occupation and purpose of existence was seemingly to blow large profits for the distributor.”

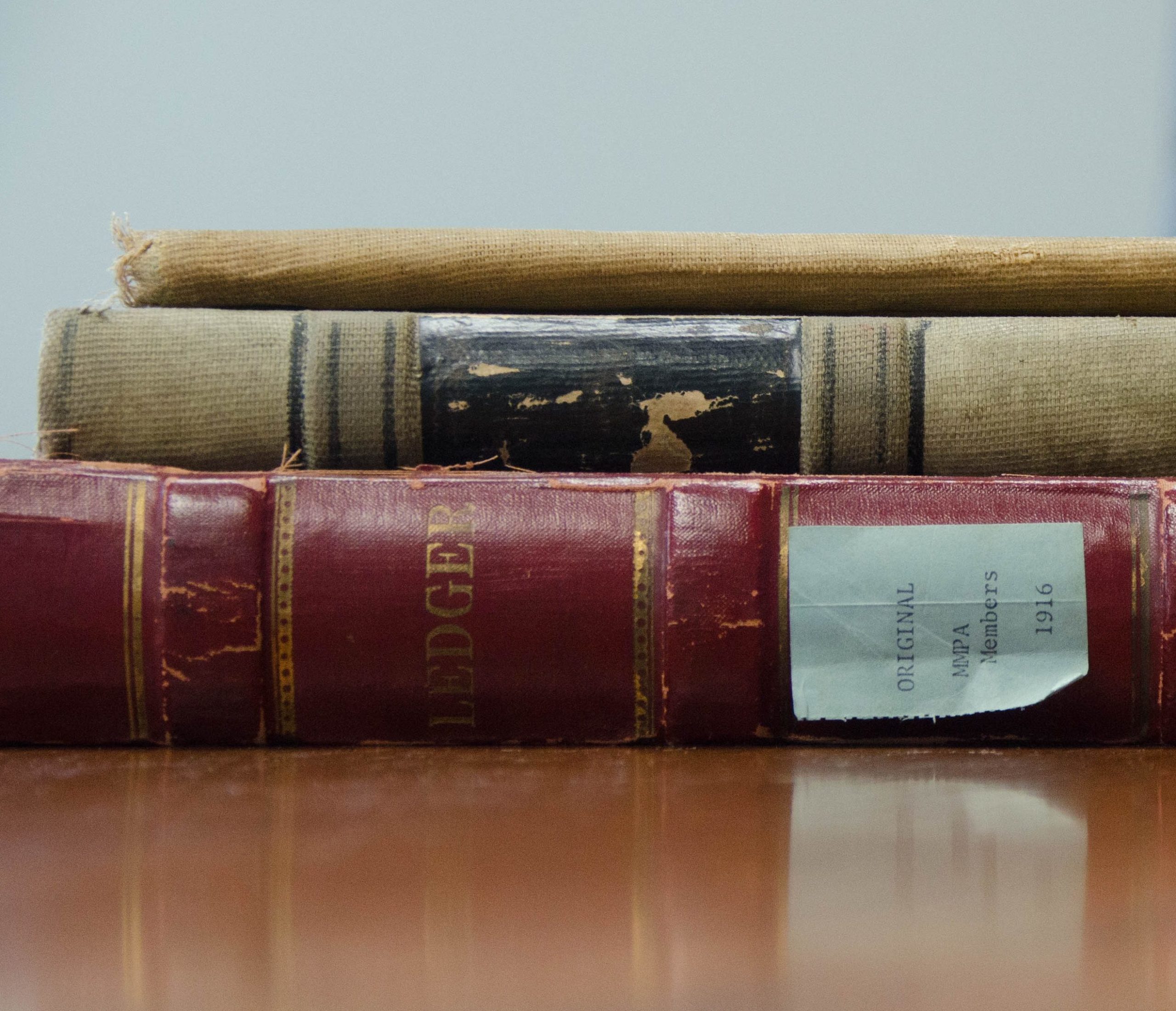

With a primary goal of securing a better price for producers’ milk, a statewide organization open only to dairy farmers was born. It would be called the Michigan Milk Producers Association. The new association had nearly 200 dues-paying members and its first board of directors at the conclusion of the daylong meeting.

“If the temper of the … milk producers present at this meeting is evidence of the feeling existing generally among their neighbors, we believe the new organization will grow in strength and its members [will] stand shoulder to shoulder in the co-operative endeavor,” the Hoard’s story predicted.

MMPA was originally formed as a federated association — a statewide organization composed of many local associations that were autonomous, farmer-governed groups. R.C. Reed, appointed as the new association’s field secretary, had the job of organizing these local groups.

Each local association paid a $5 annual membership plus 50 cents per individual member to join the state MMPA. Individuals paid dues of $1 per year to sustain local operations.

The state association would serve as the selling agency for all member milk. The association, with member approval, set a milk price based on generating a fair return over production costs. Then, it was the association’s job to get dealers to pay the target price.

Local associations acted autonomously in most respects. Each had its own executive committee plus four other committees. The marketing committee worked with the state association to determine prices and sell the local members’ milk collectively. The herd improvement committee arranged cow testing and breeding. The sanitation and health committee led cleanliness reforms on farms and in milk barns. The cooperative purchasing committee secured feed and other supplies in carloads to save members money.

By MMPA’s first annual meeting on Oct. 17, 1916, the success in member recruiting was apparent. The auditorium in the MAC Agricultural Building was filled to overflowing as almost 1,000 milk producers “from nearly every county in Southern Michigan” attended. They represented more than 80 local associations that had formed in the few weeks since MMPA was founded. Other local associations were forming as fast as Reed could process requests.

In the 100 years that followed the first official meeting of MMPA, the methods of marketing milk and organizing the cooperative have changed, but the goals have remained the same.

This article was adapted from the newly released MMPA history book, Stronger. Together., written by Donna Abernathy. The article was originally published in the June issue of the Michigan Milk Messenger.