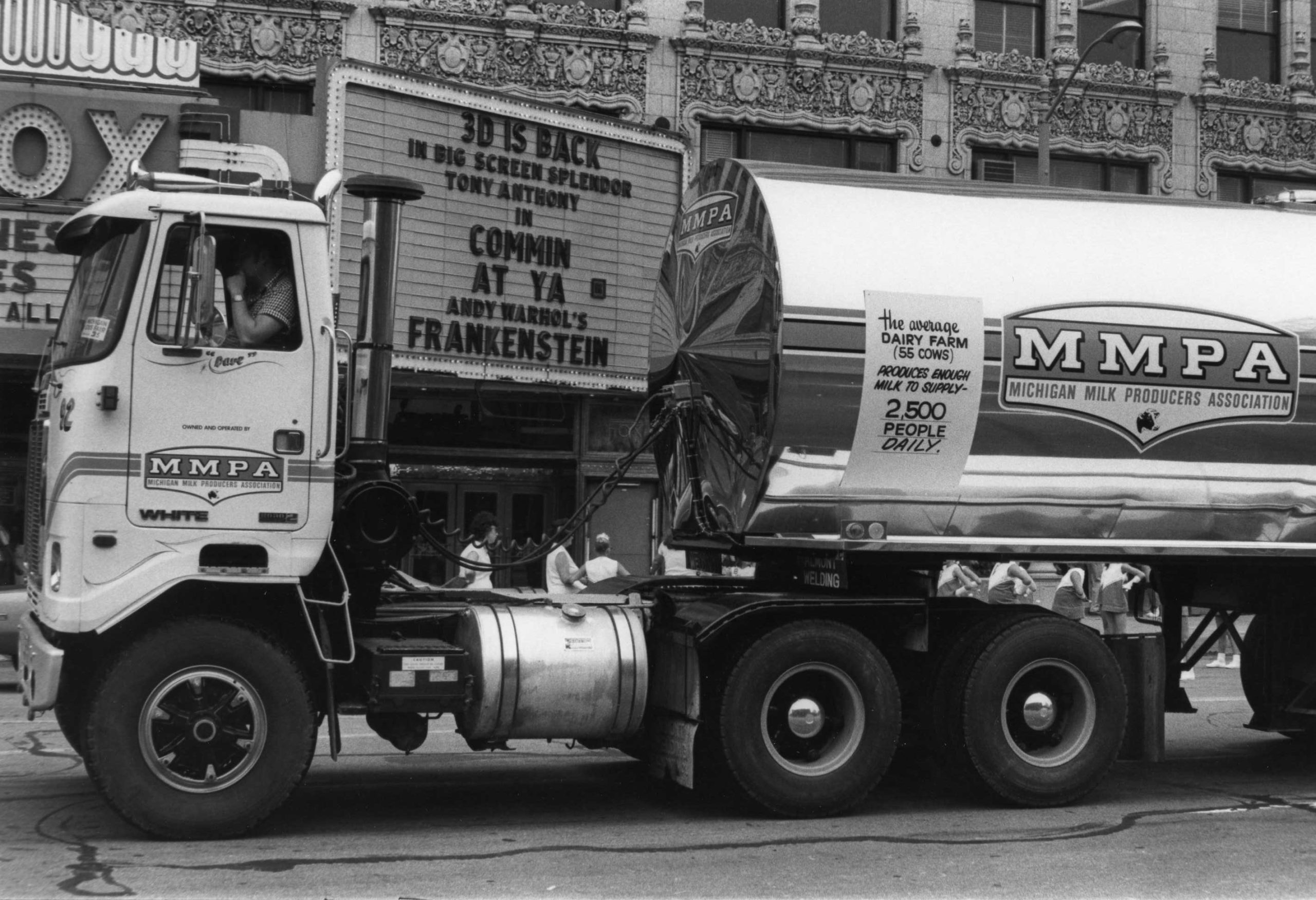

Milk trucks are a fixture on the dirt roads and highways across the nation carrying a valuable, yet perishable product for farmers and consumers alike. Milk haulers are the link from the cow that produces that white, power packed nutritional punch to the consumer who enjoys it. Milk quality is unsurpassable in today’s market but it hasn’t always been that way and we have the evolution of milk transportation to thank for it.

A century ago, when MMPA was a budding cooperative, milk was picked up in cans and transported to the processing plants by truck or by rail. The cooling systems were crude involving cold water passing over a can of milk to cool it to 60 degrees. It wasn’t until the early 1920s when the Board of Health in various cities around the state demanded that their milk providers construct a milk house on their farm to ensure a higher quality product. In an article in the Milk Messenger, August of 1920, authored by editor R.C. Reed, the following advice was given:

“One may build it [a milk house] cheaply or elaborately as desired. We have seen milk houses that answered every demand of the Board of Heath and which did not cost, for new material, more than fifteen dollars. This was in a time when lumber was somewhat cheaper than it is now, but make the calculation for yourself. Use the same apparatus for cooling which you use now; put over it a little house seven feet wide by eight feet long, with the roof nine feet high on one side and seven feet on the other; paper it within, overhead and on the sides, with any kind of remnants that can be obtained of house paper, and if necessary cover it with roofing on the sides and top.

“If possible place it under a shade tree and this as a temporary structure, until the time comes when you can build a permanent one, will satisfy the demands of the Board of Health. I recently saw one of this kind which had been built by a man and his wife and it took the two but a little over a day and a half and they had a clean place, free from germs and dust, away from the heat of the sun, and had as nice a quality of milk as could have been produced or kept in a milk house costing one hundred times the amount this one cost.”

But by May of 1931, the Milk House Requirements for the Detroit markets were hard and fast for producers, requiring them to have a milk house that could be used year round and completely sealed on the inside. If they did not satisfy these requirements, they would not be issued a permit.

While milk house rules were changing, the path from farm to the plant was the same. According to former MMPA leader Jack Barns the movement of milk went directly to processing plants in the secondary markets but almost all of the milk for the Detroit processors was delivered in cans to MMPA receiving stations scattered across southern Michigan. From the receiving stations, the milk was loaded into over-the-road tankers for shipment to the processing plant.

The first milk trucks had no cover or protection for the milk but that changed in the 1930s when insulated trucks came on the scene and cans were hauled by muscle bound milk men slinging eighty pound milk cans from the truck into the plant. It wasn’t until the 1950s that bulk trucks came on the scene and suddenly routes changed, more milk could be hauled by one truck and milk quality improved exponentially.

Because milk haulers frequented farms, they were almost like family to the farmer. The same hauler came down the same routes, picking up the same farmers milk, sometimes for decades. Christmas, Easter, Thanksgiving, snow, rain, ice, sleet, the day didn’t matter because the milk had to be hauled.

The Traver family of Williamston was an example of this longevity. The Travers were in it for the long haul with four generations of milk haulers in the family. Hailing from Williamston, George Traver hitched up his horse and buggy and began hauling milk in 1904. In 1927, George passed the route on to his son Marc Traver who experienced several decades of MMPA history.

When the Great Depression arrived, times were tough everywhere. Marc Traver and other milk haulers around the state had the responsibility of delivering milk checks to the producers. In one instance in 1933, the banks in Detroit closed before the farmers checks were delivered. Traver had cashed his check in Fowlerville and when he delivered the ‘bad checks’ to the farmers he was able to give them each a small loan until their checks were cashed. According to Traver, the milk checks backed by MMPA were always good.

From tornado trashed routes to snow drifts that made roads impassable, to muddied drives that required tractors for extrication from the farm yard, milk haulers continue to be an invaluable asset from farm to table.

A century of MMPA could only happen with a century of reliable transportation taking the farmers hard earned product to a broad population in need of the natures perfect nutrient-dense delicious delight: Milk.

–Melissa Hart

This article originally appeared in the February 2016 issue of the Michigan Milk Messenger.