Women have been influential from the beginning of time. Eve influenced Adam to take a bite of the forbidden fruit and the world as they knew it was turned upside down.

Just as the diversification of women’s roles have evolved through history, the farmwife has woven her way into every level of leadership in the 100-year existence of Michigan Milk Producers Association. The woman on the farm in 2016 paints an entirely different portrait than her comrade of 1916. But the tenacity, passion and determination that frame her soul are the same last century and today.

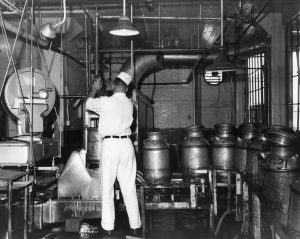

In 1916, the challenges were different. Faced with few modern conveniences on the farm, her daily chores took longer than the daily activity today. Add the cooking on a woodstove and harvesting and canning to feed the family, she was also expected to take up the slack in the fields and the barn. The lure of the big city was not unique to the most recent generation of farm kids. In the early 20th century, the bright lights of the big city and promise of employment led young men off the farm leaving the younger children and the farm wife to keep all the plates spinning.

Jennifer Lewis, wife of Bruce Lewis of Pleasant View Dairy of Jonesville, a longtime member of MMPA, paints the picture of the early century farm wife,

“Women of that era were educators, doctors and magicians. They could do just about anything and there were times they had to do everything. Our farm has been in the Lewis family for 75 years this year. Bruce’s Grandmother, Vivian, went to college to be a teacher, graduating from OSU in 1928 (one of just a handful). When she wasn’t teaching, she did it all. They had a few cows, sheep, chickens and hogs. She milked, fed, scattered and slopped.”

The role of women on the farm was central to success and MMPA discovered their value early on during the Depression. Milk prices were low, feed prices were high and spirits were hopeless. In April of 1935 the first “Home Page” appeared in the Michigan Milk Messenger and women’s credibility was spelled out by writer Margaret Sheehy.

“The Messenger has long appreciated the influence of the woman in Association affairs. It is generally conceded that women are concerned over the family income. They naturally are interested in producing milk of such a quality that it will net the most money for the product. There is too, a universal accepted fact that women possess a keen sense of understanding. The producer husbands and sons, members of this organization, were imbued with a sense of appreciation of cooperative principles—yet we believe that it was the intuition on the part of the wives and mothers that helped them to interpret the contract and know that the Association was their business organization. “

In 1936 women were invited for the first time to meet with the Sales Committee and Dairy Council. And ten years later, Mrs. Martin Montgomery posed the question in an article for the Michigan Milk Messenger, “How Active Should Women Be in the MMPA?”

She wrote:

“So long as she is such an important cog in the wheel of farm management and since milk is the most important source of income on our farms today, why shouldn’t she have an active part in the association that controls the farmer’s income?”

But it wasn’t until 1975 that the Imlay City MMPA Local would trust their voice to a woman, Joan Beatty as the first female delegate to the MMPA annual meeting. Joan and her husband Ron moved from the Detroit suburbs to Imlay City start a farm in 1970. While she had a lot to learn about running a farm, she said she had never been afraid to take on something new.

That ‘no-fear’ factor surfaced again in 1986 in the first female board of director Deanna Stamp from Marlette. With a long MMPA family history, Deanna and her husband were in partnership with her brother when she realized the importance of the cooperative structure and milk marketing. She had the opportunity to run and was elected to the board. She commented, “Maybe I was naive but I think I stepped into that role feeling as an equal and I was treated as an equal.” Serving from 1986 – 2009 she said, “It was an easy transition for me, I felt like I was a part of the board and it was a great experience.”

Today the role of women on the farm reflects the educational importance they have layered on top of their determination and desire to produce a quality product out of a livelihood they were created for. And her zeal for leadership roles within the 100-year-old milk cooperative is even stronger.

Cami Martz-Evans, wife of Carlton Evans on the three generation MMPA member family farm in Litchfield summed a woman’s role today: “She will struggle in the heat, freeze in the cold, spit out bugs, inhale dust, and keep going during harvest. She will raise her child and worry about their grades, their future, and what they need to be successful like every other woman has for 100 years. She will be a dairy farmer ‘with MMPA’. Which means she’ll be a DIVA on a dirt road in her world. Just like 100 years of women before her.”